You may want to forget everything you learned during your childhood obsession with the Tyrannosaurus Rex. A review of thousands of fossils and a new theory announced Wednesday may topple a 130-year-old family tree of dinosaur relations.

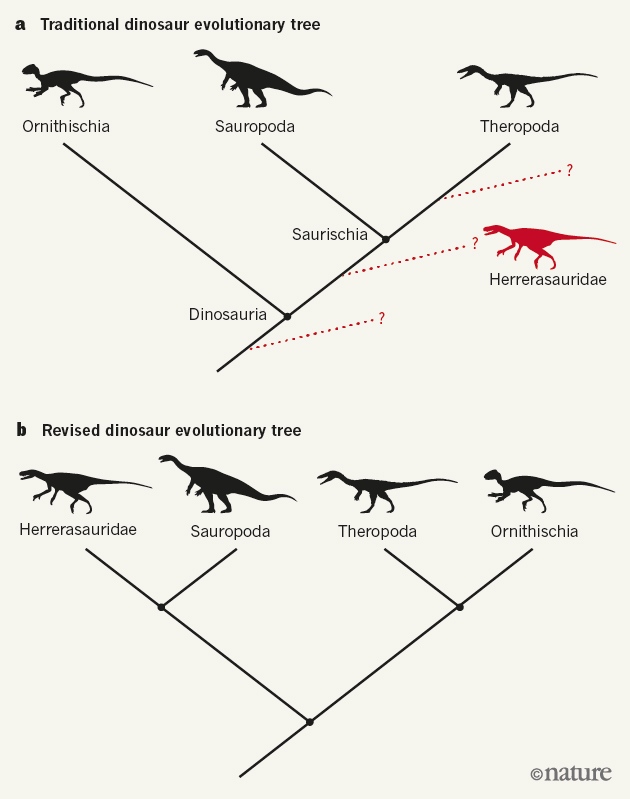

Since 1888, paleontologists labored under a classification system that divided the prehistory species into two distinct categories based on the structure of their pelvic bones: the bird-hipped vegetation eaters known as Ornithischia and the reptile-hipped Saurischia, which included both carnivores and herbivores.

Now, a revolutionary new hypothesis says the relationships between the major groups of dinosaurs need radical reorganization. If confirmed, old branches of the dinosaur family tree may be pruned off and new ones created

.

"We completely reshape the dinosaur family tree," said study lead author Matthew Baron of the United Kingdom's University of Cambridge.

After careful analysis of dozens of fossil skeletons and tens of thousands of anatomical characters, researchers concluded these long-accepted groups may, in fact, be wrong and the traditional names need to be altered.

For example, while the T-rex remains in Theropoda, that entire branch of the tree shifts on the chart to indicate those species are more closely related to the Ornithischia line than Saurischia, Baron said.

Saurischia still includes Sauropoda, such as the Brontosaurus. However, the study also indicates a more archaic group, the carnivorous Herrerasauridae, also stems from Saurischia. "This conclusion came as quite a shock since it ran counter to everything we'd learned," he said.

The study also offers new clues about dinosaur evolution, including that early dinosaurs were omnivorous, small, walked on two legs and used grasping hands. It also found dinosaurs popped up 247 million years ago — 10 million years earlier than the standard theory — with a fossil from Tanzania in East Africa.

Baron said researchers involved in the study, published in the peer-reviewed British journal Nature, are open to the possibility the conclusions could be "wrong, either wholly or partly."

"It must be tested and reviewed by others," he said. "I personally can’t wait for the debate that this will cause in the field and I look forward to a lively and hopefully civil exchange of ideas and evidence in the coming years."

The analysis builds on previous ones involving other researchers but is original in many respects, according to Kevin Padian, a University of California, Berkeley, paleontologist, who told Science magazine he is intrigued but reserving further judgment.

The new picture is "plausible, but not a slam-dunk," Stephen Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh told Science, noting the tree shuffle isn't based on new fossils, but on an analysis of existing specimens. "It would be cool if they're right, (but) there's a big burden of proof when you're going against a long legacy in the literature."

(USA Today)