In 1893 the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen embarked on a mission of extraordinary boldness and ingenuity. He planned to become the first person to reach the north pole by allowing his wooden vessel, the Fram, to be engulfed by sea ice and pulled across the polar cap on an ice current.

Ultimately, Nansen ended up abandoning the Fram and skiing hundreds of miles to a British base after he realised he was not on course to hit the pole, but the ship made it across the ice cap intact and the expedition resulted in groundbreaking scientific discoveries about the Arctic and weather patterns.

Now, more than a century on, scientists are planning to retrace this epic voyage for the first time, in the most ambitious Arctic research expedition to date.

The Mosaic (Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate) mission will be the first since Nansen’s to traverse the polar ice cap by ship and will aim to answer big questions about the Arctic, including why the region is warming faster than any other place on Earth.

During the year-long, 1,500-mile trip, teams of scientists – protected from polar bears by armed guards – will disperse across the polar cap to take measurements and make reports that have never been possible before.

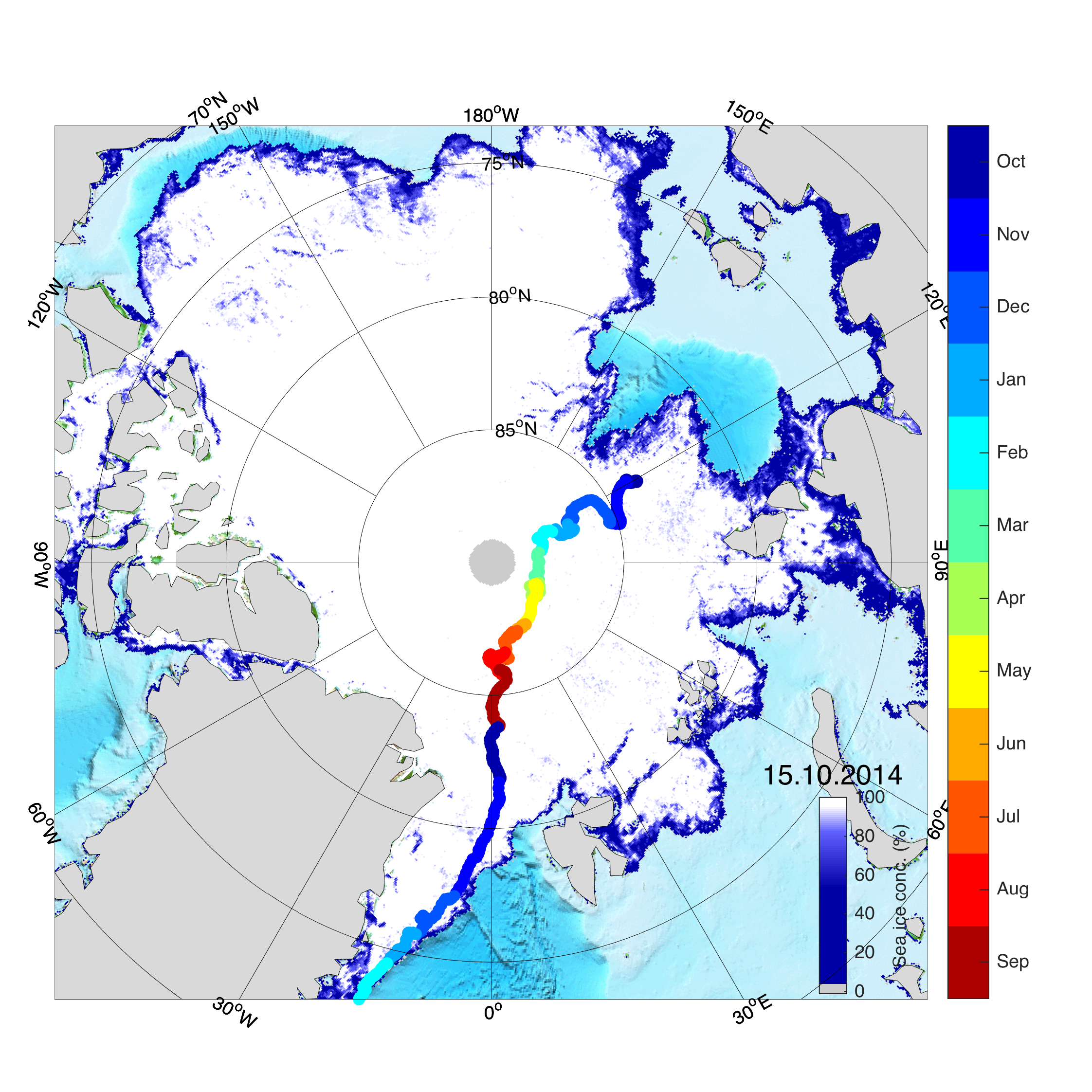

The mission’s co-leader Prof Markus Rex, of the Alfred Wegener Institute in Potsdam, Germany, said: “The plan is to travel in summer 2019, when sea ice is thin and its extent is much smaller. We can make our way with our icebreaker Polarstern into the thin sea ice to the Siberian sector of the Arctic. Then we stop the engines and let the Polarstern drift with the sea ice.”

By November the vessel will be encased in solid sea ice, temperatures will plunge to as low as -50C and the darkness of polar night will set in. In these hostile conditions, the scientists will set up an extensive network of research stations, in some cases travelling 50km from the vessel on snow mobiles.

Speaking at the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s (AAAS) annual meeting in Boston on Sunday, Rex outlined new details of the €50m (£42m) project, which will involve 50 institutions from 14 countries including the UK, US and Russia.

The teams will investigate how rapid warming in the Arctic is altering the polar vortex. Scientists anticipate that as the temperature contrast between low and high latitudes reduces, strong circular winds around the pole will shift to lighter, more meandering patterns. This will allow “more frequent and cold air outbreaks from the Arctic”, causing extreme cold spells on the east coast of the US and parts of Europe.

The scientists will release hundreds of helium balloons carrying sensors to take atmospheric measurements of super-cooled water in clouds, a unique Arctic phenomenon. Water droplets in the clouds reach temperatures as low as -10C without freezing, partly due to the pristine Arctic air, which is low in aerosols that would usually seed the formation of ice crystals in such temperatures. Increasing industrial activity in the Arctic could radically alter this process, Rex said.

The Northern Sea Route Information predicts that 20 years from now, 25% of container shipping from Asia to Europe will go through the Arctic rather than through the Suez canal.

Mission scientists who will work onboard the Polarstern in three-month rotations will also investigate life in melt ponds, small lakes that form on the ice in spring. “Once the sea ice breaks up in spring, there are huge algal blooms and within a few days the ocean is green,” said Rex. “Somehow the phytoplankton and the krill survives under the ice, it’s doing something in mid-winter under the ice.”

What happens in the Arctic has a major impact on the weather in northern Europe and North America. Yet the forces at work are not well understood, because gaining access to the region to carry out ground-based studies is so difficult, limiting the accuracy of forecasting and leaving major gaps in what climate models can explain.

Recorded levels of Arctic sea ice, which reached the second lowest minimum on record last summer, show a much faster rate of decline than computer simulations predict, for instance.

“There are many many really small-scale processes which affect the climate on a regional and global scale in the Arctic which we can’t observe from a satellite,” said Rex.

As the polar winter turns to spring, the Polarstern will approach the Fram Strait, the body of water between Greenland and Svalbard where Nansen’s vessel eventually made its exit into open water. “Only the Fram has done this before,” said Rex.

The Mosaic team believe the latest mission, while less perilous, could have a similarly revolutionary impact on the scientific understanding of the Arctic.

Matthew Shupe, a scientist at the University of Colorado who is co-leading the mission, said: “[The Fram] was groundbreaking in its era and frankly in it’s own way Mosaic will be in this era. It will be this very momentous step forward.”

(The Guardian)