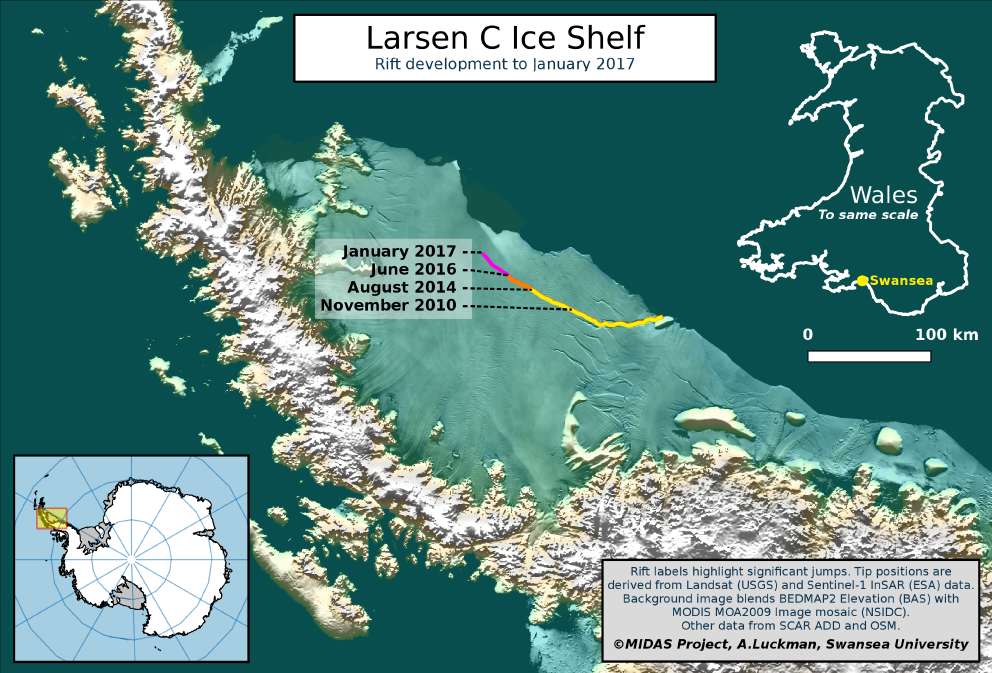

An iceberg, one of the 10 largest known to science, is about to break away from Antarctica. The Larsen C ice shelf has been breaking away from the southern continent for some time now, but an enormous crack is threatening to calve off a 5,000-square-kilometer (1,931 square miles) segment of it.

The canyon has been around for some time, but in the last month or so, it has proliferated at a breakneck pace. In the second half of December 2016, it grew by a whopping 18 kilometers (11.2 miles). Now, a massive piece of ice is being held back by just a 20-kilometer-long (12.4 miles) stretch of ice.

The entire Larsen C ice shelf – one about twice the size of Hawaii – is not due to collapse, but this crack will cleave off about 10 percent of it. Scientists are concerned that this will make the surviving parts of Larsen C incredibly unstable and highly prone to collapse within the next decade or so.

Larsen C is the most significant ice shelf in northern Antarctica. It’s already floating on the ocean, so its destruction won’t directly contribute to sea level rise itself. However, it is holding back a lot of land-based glaciers.

When Larsen C completely disintegrates, the floodgates will open, and this ice will inexorably tumble into the sea and increase global sea levels by about 10 centimeters (3.9 inches). That may not sound like too much, but consider the fact that the global sea level rise over the last 20 years has been about 6.6 centimeters (2.6 inches).

Combined with the sea level rise being generated as a result of man-made climate change, Larsen C’s contribution is certainly nothing but significant.

Mapping the calving of Larsen C's iceberg. MIDAS/Swansea University/Aberystwyth University

Although the increasingly rapid warming of the region has likely accelerated the progression of the gigantic crevasse cleaving parts of Larsen C away from Antarctica, there is no direct evidence to support this just yet. There is, however, plenty of evidence linking warmer atmospheric and ocean temperatures to ice shrinkage elsewhere on the continent.

Researchers from Swansea University, who’ve been using satellite data to monitor its demise, note that this particular calving is an inevitable event due to the unique geography of the region.

“If it doesn't go in the next few months, I'll be amazed,” project leader Adrian Luckman, a professor of geography at Swansea University, told BBC News.

The Antarctic Peninsula used to house a network of ice shelves under the Larsen name. Larsen A collapsed in 1995, and Larsen B crumbled quite dramatically back in 2002. In fact, there are plenty of ice shelves all over Antarctica that are on the edge of disaster right now, but it’s now certain that Larsen C, the last of its namesake, will go first.